A big appreciation to Chris Schild (@SchildChris on Twitter) for archiving this article!

Article: Discoveries, April 1991

by Allan Vorda

The interview originally appeared in DISCoveries magazine, April 1991, and then in Allan’s book “Psychedelic Psounds: Interviews from A to Z with ’60s Psychedelic and Garage Bands” (Borderline Productions/U.K., 1994).

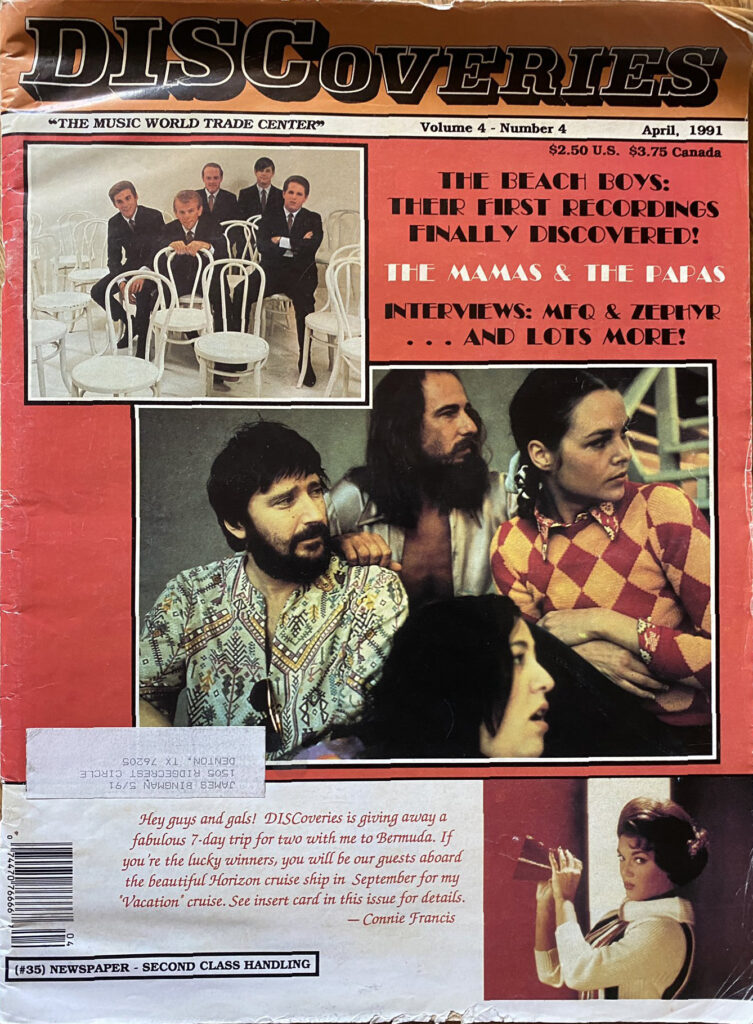

Zephyr was formed in Boulder, Colorado in late 1968 and consisted of Candy Givens (lead vocals and harmonica), David Givens (bass and vocals), Tommy Bolin (lead guitar and vocals), John Faris (piano, organ, flute), and Robbie Chamberlin (drums and vocals).

The band was a conglomeration of different musical styles that could play rock, blues, and jazz. The first album, simply titled Zephyr, shows the incredible range of music they could play in such songs as “Cross the River,” “St. James Infirmary,” and “Hard Chargin’ Woman.” The members’ musical abilities consisted of the classical training of Faris, the steady drumming of Chamberlin, and the hardly noticeable but excellent bass patterns of David Givens (listen to his jazzy bass runs in “Huna Buna” and “Cross the River”).

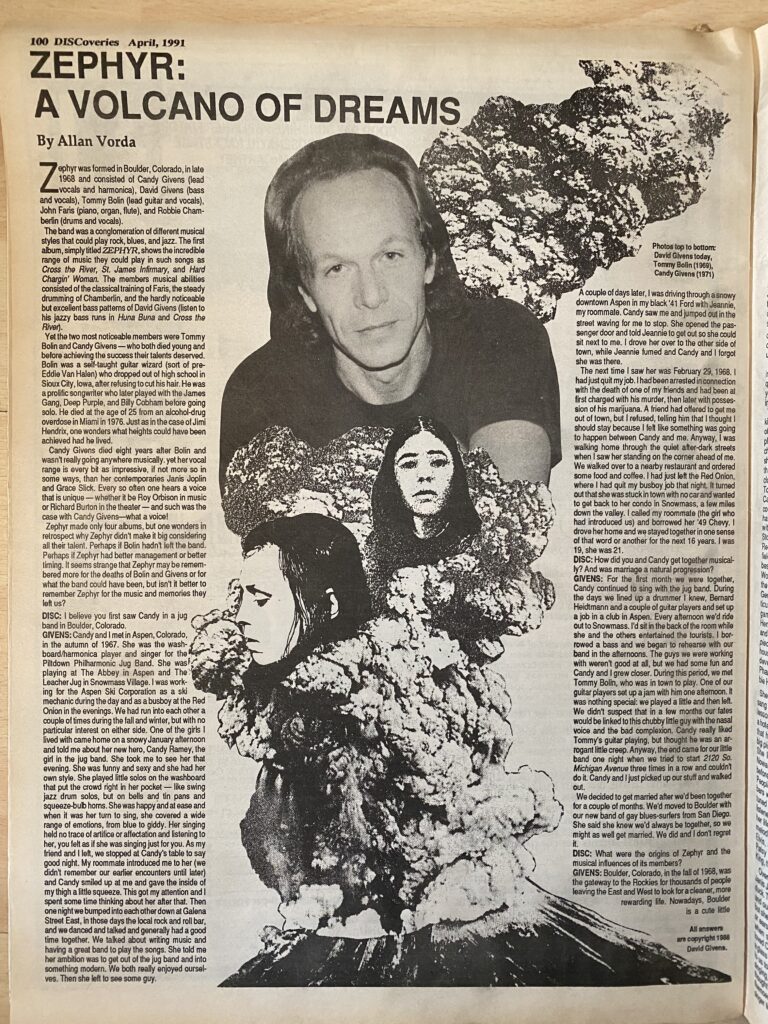

Yet the two most noticeable members were Tommy Bolin and Candy Givens — who both died young and before achieving the success their talents deserved. Bolin was a self-taught guitar wizard (sort of pre-Eddie Van Halen) who dropped out of high school in Sioux City, Iowa, after refusing to cut his hair. He was a prolific songwriter who later played with the James Gang, Deep Purple, and Billy Cobham before going solo. He died at the age of twenty-five from an alcohol-drug overdose in Miami in 1976. Just as in the case of Jimi Hendrix, one wonders what heights could have been achieved had he lived.

Candy Givens died eight years after Bolin and wasn’t really going anywhere musically, yet her vocal range is every bit as impressive, if not more so, than her contemporaries Janis Joplin and Grace Slick. Every so often one hears a voice that is unique — whether it is Roy Orbison in music or Richard Burton in the theater — and such was the case with Candy Givens. What a voice!

Zephyr made only four albums, but one wonders in retrospect why Zephyr didn’t make it big considering all their talent. Perhaps if Bolin hadn’t left the band. Perhaps if Zephyr had better management or better timing. It seems strange that Zephyr may be remembered more for the deaths of Bolin and Givens or for what the band could have been, but isn’t it better to remember Zephyr for the music and memories they left us?

The following interview was conducted with David Givens on 4/1/88.

AV: I believe you first saw Candy in a jug band in Boulder.

DG: Candy and I met in Aspen, Colorado, in the Autumn of 1967. She was the washboard/ harmonica player and singer for the Piltdown Philharmonic Jug Band. They were playing at The Abbey in Aspen and The Leather Jug in Snowmass Village. I was working for the Aspen Ski Corporation as a ski mechanic during the day and as a busboy at the Red Onion in the evenings. We had run into each other a couple of times during the fall and winter, but with no particular interest on either side. One of the girls I lived with came home on a snowy January afternoon and told me about her new hero, Candy Ramey, the girl in the jug band. She took me to see her that evening. She was funny and sexy and she had her own style. She played little solos on the washboard that put the crowd right in her pocket — they sounded like swing jazz drum solos, but on bells and tin pans and squeeze-bulb horns. She was happy and at ease and when it was her turn to sing, she covered a wide range of emotions, from blue to giddy. Her singing was unaffected and, listening to her, you felt as if she was singing just for you. As my friend and I left, we stopped at Candy’s table to say good night. My roommate introduced me to her (we didn’t remember our earlier encounters till later) and Candy smiled up at me and gave the inside of my thigh a little squeeze. This got my attention and I spent some time thinking about her after that. Then one night we bumped into each other down at Galena Street East, in those days the local rock and roll bar, and we danced and talked and generally had a good time together. We talked about writing music and having a great band to play the songs. She told me that her ambition was to get out of the jug band and into something modern. We both really enjoyed ourselves. Then she left to see some guy.

A couple days later, I was driving through a snowy downtown Aspen in my black ’41 Ford with Jeannie, my roommate. Candy saw me and jumped out in the street waving for me to stop. She opened the passenger door and told Jeannie to get out so she could sit next to me. I drove her over to the other side of town, while Jeannie fumed and Candy and I forgot she was there.

The next time I saw her was February 29, 1968. I had just quit my job. I had been arrested in connection with the death of one of my friends and had been at first charged with his murder, then later with possession of his marijuana. A friend had offered to get me out of town, but I refused, telling him that I thought I should stay because I felt like something was going to happen between Candy and me. Anyway, I was walking home through the quiet after-dark streets when I saw her standing on the corner ahead of me. We walked over to a nearby restaurant and ordered some food and coffee. I had just left the Red Onion, where I had quit my busboy job that night. It turned out that she was stuck in town with no car and wanted to get back to her condo in Snowmass, a few miles down the valley. I called my roommate (the girl who had introduced us) and borrowed her ’49 Chevy. I drove her home and we stayed together in one sense of that word or another for the next sixteen years. I was nineteen, she was twenty-one.

AV: How did you and Candy get together musically? And was marriage a natural progression?

DG: For the first month we were together, Candy continued to sing with the jug band. During the days we lined up a drummer I knew, Bernard Heidtmann, and a couple of guitar players and set up a job in a club in Aspen. Every afternoon we’d ride out to Snowmass.

I’d sit in the back of the room while she and the others entertained the tourists. I borrowed a bass and we began to rehearse with our band in the afternoons. The guys we were working with weren’t good at all, but we had some fun and Candy and I grew closer. During this period, we met Tommy Bolin, who was in town to play. One of our guitar players set up a jam with him one afternoon. It was nothing special: we played a little and then left. We didn’t suspect that in a few months our fates would be linked to this chubby little guy with the nasal voice and the bad complexion. Candy really liked Tommy’s guitar playing, but thought he was an arrogant little creep. Anyway, the end came for our little band one night when we tried to start “2120 So. Michigan Ave.” three times in a row and couldn’t do it. Candy and I just picked up our stuff and walked out.

We decided to get married after we’d been together for a couple of months. We’d moved to Boulder with our new band of gay blues-surfers from San Diego. She said she knew we’d always be together, so we might as well get married. We did and I don’t regret it.

AV: What were the origins of Zephyr and the musical influences of its members?

DG: Boulder, Colorado, in the fall of 1968, was the gateway to the Rockies for thousands of people leaving the East and West to look for a cleaner, more rewarding life. Nowadays, Boulder is a cute little Disneylandesque example of why homosexuals shouldn’t plan cities, but twenty years ago it still had a couple of rough edges left. The popular bands in town were the Leopold Fuchs Hate Band and Black Pearl. Drugs, parachutes, skis, mountain climbing gear, motorcycles, and waterbeds were the popular recreational toys of the day. Tommy and John Faris had come to town shortly after we did, in the fall of 1968. They had a band called Ethereal Zephyr, playing some loud jazzy music. Tommy and John were great friends and John was a very big influence on Tommy. Tommy grew up in Sioux City, Iowa, listening to the radio like many midwestern kids did. His big influences from the world of rock and roll were Elvis, Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles primarily, though he was very knowledgeable about the old rock and blues records. He was very fond of Wes Montgomery’s guitar work. Faris was one of the most talented musicians it has ever been my pleasure to work with. He knew everything about chords and harmony. Tommy was a natural mimic, he could play anything he heard, but he had no real musical base before he met John. John’s rock tastes ran toward Tommy James and Steppenwolf, but he introduced Tommy to John Coltrane, Jack McDuff, and McCoy Tyner and on and on. Tommy and John could play together spontaneously without any self-consciousness because they respected each other very much. The rest of their band was OK, but Tommy and John were both unusual and very entertaining.

Otis Taylor, at that time a young, black blues artist in Denver, taught Tommy a lot of blues guitar techniques. He and Tommy were good friends for many years and Otis continued to influence Tommy’s taste in the arts, music in particular.

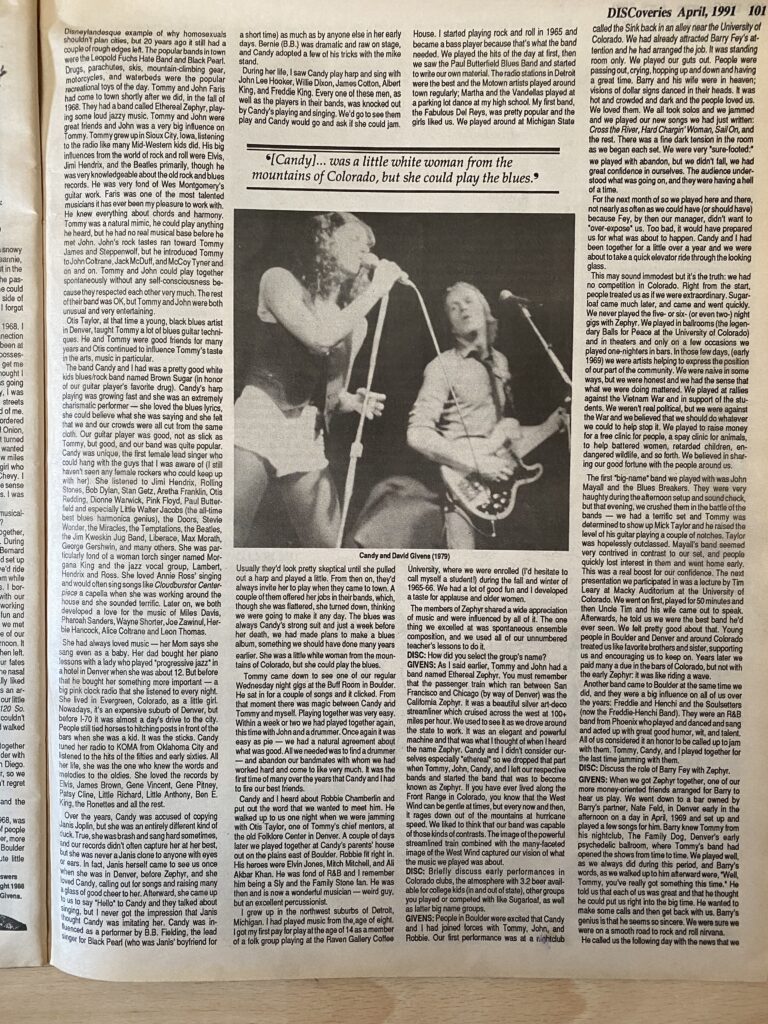

The band Candy and I had was a pretty good white kid blues/rock band named Brown Sugar (in honor of our guitar player’s favorite drug). Candy’s harp playing was growing fast and she was an extremely charismatic performer — she loved the blues lyrics, she could believe what she was saying and she felt that we and our crowds were all cut from the same cloth. Our guitar player was good, not as slick as Tommy, but good, and our band was quite popular. Candy was unique, the first female lead singer who could hang with the guys that I was aware of (I still haven’t seen any female rockers who could keep up with her). She listened to Jimi Hendrix, Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Stan Getz, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Dionne Warwick, Pink Floyd, Paul Butterfield and especially Little Walter Jacobs (the all-time best blues harmonica genius), the Doors, Stevie Wonder, the Miracles, the Temptations, the Beatles, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, Liberace, Max Morath, George Gershwin, and many others. She was particularly fond of a woman torch singer named Morgana King and the jazz vocal group, Lambert, Hendrix, and Ross. She loved Annie Ross’ singing and would often sing songs like “Cloudburst” or “Centerpiece” a capella when she was working around the house and she sounded terrific. Later on, we both developed a love for the music of Miles Davis, Pharoah Sanders, Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, Herbie Hancock, Alice Coltrane, and Leon Thomas.

She had always loved music — her mother says she sang even as a baby. Her dad bought her piano lessons with a lady who played “progressive jazz” in a hotel in Denver when she was about twelve. But before that he bought her something more important — a big pink clock radio that she listened to every night. She lived in Evergreen, Colorado as a little girl. Nowadays, it’s an expensive suburb of Denver, but before I-70 it was almost a day’s drive to the city. People still tied horses to the hitching posts in front of the bars when she was a kid. It was the sticks. Candy tuned her radio to KOMA from Oklahoma City and listened to the hits of the 50s and early 60s. All her life, she was the one who knew the words and melodies to the oldies. She loved the records by Elvis, James Brown, Gene Vincent, Gene Pitney, Patsy Cline, Elvis, Little Richard, Little Anthony, Ben E. King, the Ronnettes, and all the rest.

Over the years, Candy was accused of copying Janis Joplin, but she was an entirely different kind of duck. True, she was brash and sang hard sometimes, and our records didn’t often capture her at her best, but she was never a Janis clone to anyone with eyes or ears. In fact, Janis, herself, came to see us once when she was in Denver, before Zephyr, and she loved Candy, calling out for songs and raising many a glass of good cheer to her. Afterward, she came up to say ”Hello” to Candy and they talked about singing, but I never got the impression that Janis thought Candy was imitating her. Candy was influenced as a performer by B.B. Fielding, the lead singer for Black Pearl (who was Janis’ boyfriend for a short time) as much as by anyone else in her early days. Bernie (B.B.) was dramatic and raw on stage, and Candy adopted a few of his tricks with the mike stand.

During her life, I saw Candy play harp and sing with John Lee Hooker, Willie Dixon, James Cotton, Albert King, and Freddie King. Every one of these men, as well as the players in their bands, was knocked out by Candy’s playing and singing. We’d go to see them play and Candy would go up and ask if she could jam. Usually they’d look pretty skeptical until she pulled out a harp and played a little. From then on, they’d always invite her up to play when they came to town. A couple of them offered her jobs in their bands, which, though she was flattered, she turned down, thinking we were going to make it any day. The blues was always Candy’s strong suit and just a week before her death, we had made plans to make a blues album, something we should have done many years earlier. She was a little white woman from the mountains of Colorado, but she could play the blues.

Tommy came down to one of our regular Wednesday night gigs at the Buff Room, in Boulder. He sat in for a couple of songs and it clicked. From that moment there was magic between Candy and Tommy and myself. Playing together was very easy. Within a week or two we had played together again, this time with John and a drummer. Once again it was easy as pie — we had a natural agreement about what was good. All we needed was to find a drummer… and abandon our bandmates with whom we had worked hard and come to like very much. It was the first time of many over the years that Candy and I had to fire our best friends.

Candy and I heard about Robbie Chamberlin and put out the word that we wanted to meet him. He walked up to us one night when we were jamming with Otis Taylor, one of Tommy’s chief mentors, at the old Folklore Center in Denver. A couple days later we played together at Candy’s parents house out on the plains, east of Boulder. Robbie fit right in. His heroes were Elvin Jones, Mitch Mitchell, and Ali Akbar Khan. He was fond of R&B and I remember him being a Sly and the Family Stone fan. He was then and is now a wonderful musician — weird guy, but an excellent percussionist.

I grew up in the northwest suburbs of Detroit, Michigan. I had played music from the age of eight. I got my first pay for play at fourteen as a member of a folk group, the Committee, playing at the Raven Gallery coffee house. I started playing rock and roll in 1965 and I became a bass player because that’s what the band needed. We played some oldies and the hits of the day at first, then we saw the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and started to play some blues and write our own material. The radio stations in Detroit were the best and the Motown artists played around town regularly. Martha and the Vandellas played at a parking lot dance at my high school. My first band, the Fabulous Del Reys, was pretty popular and the pretty girls liked us. We played around at Michigan State University, where we were all enrolled (I’d hesitate to call myself a student!) during the fall and winter of 1965-66. We had a lot of good fun and I developed a taste for applause and older women.

The members of Zephyr shared a very wide appreciation of music and were influenced by all of it. The one thing we excelled at was spontaneous ensemble composition, and we used all of our un-numbered teachers’ lessons to do it.

AV: How did you select the group’s name? The dictionary definition of Zephyr refers to a God personifying a gentle west wind as well as “any air, insubstantial, or passing thing.”

DG: As I said earlier, Tommy and John had a band named Ethereal Zephyr. You must remember that the passenger train which ran between San Francisco and Chicago (by way of Denver) was the California Zephyr. It was a beautiful silver art-deco streamliner which cruised across the West at 100 plus miles per hour. We used to see it as we drove around the state to work. It was an elegant and powerful machine and that was what I thought of when I heard the name Zephyr. Candy and I didn’t consider ourselves especially “ethereal,’’ so we dropped that part when Tommy, John, Candy, and I left our respective bands and started the band that was to become known as Zephyr. If you have ever lived along the Front Range in Colorado, you know that the West wind can be gentle at times, but every now and then, it rages down out of the mountains at hurricane speed. We liked to think that our band was capable of those kinds of contrasts. The image of the powerful streamlined train combined with the many-faceted personality of the West wind embodied our vision of the music we played.

AV: Briefly discuss early performances in Colorado clubs, the atmosphere with 3.2 beer available for college kids, other groups you played or competed with (e.g., Sugarloaf, etc.), as well as later big name groups.

People in Boulder were excited that Candy and I had joined forces with Tommy, John, and Robbie. Our first performance was at a nightclub called the Sink, back in an alley near the University of Colorado. We had already attracted Barry Fey’s attention and he had arranged the job. It was standing room only. We played our guts out. People were passing out, crying, hopping up and down, and having a great time. Barry and his wife were in Heaven; visions of dollar signs danced in their heads. It was hot and crowded and dark and the people loved us. We loved them. We all took solos and we jammed and we played our new songs we had just written: “Cross the River,” “Hard Chargin’ Woman,” “Sail On” and the rest. There was a fine dark tension in the room as we began each set. We were very sure-footed: we played with abandon, but we didn’t fall; we had great confidence in ourselves. The audience understood what was going on, and they were having a hell of a time.

For the next month or so we played here and there, not nearly as often as we could have (or should have) because Fey, by then our manager, didn’t want to “over-expose us.” Too bad, it would have prepared us for what was about to happen. Candy and I had been together for a little over a year and we were about to take a quick elevator ride through the looking glass.

This may sound immodest but it’s the truth: we had no competition in Colorado. Right from the start, people treated us as if we were extraordinary. Sugarloaf came much later, and came and went quickly. We never played the five or six (or even two) night gigs with Zephyr. We played in ballrooms (the legendary Balls for Peace at the University of Colorado) and in theatres and only on a few occasions we played one-nighters in bars. In those days (early 1969), we were artists helping to express the position of our part of our community. We were naive in some ways, but we were honest and we had the sense that what we were doing mattered. We played at rally’s against the Vietnam War and in support of the students. We weren’t real political, but we were against the War and we believed that we should do whatever we could to help stop it. We played to raise money for a Free Clinic for people, a Spay Clinic for animals, to help Battered Women, Retarded Children, Endangered Wildlife, and so forth. We believed in sharing our good fortune with the people around us.

The first “big-name” band we played with was John Mayall and the Blues Breakers. They were very haughty during the afternoon setup and sound check, but that evening, we crushed them in the battle of the bands — we had a terrific set and Tommy was determined to show up Mick Taylor and he raised the level of his guitar playing a couple of notches. Taylor was hopelessly outclassed. Mayall’s band seemed very contrived in contrast to our set, and people quickly lost interest in them and went home early. This was a real boost for our confidence. The next presentation we participated in was a lecture by Tim Leary at Macky Auditorium at the University of Colorado. We went on first, played for fifty minutes and then Uncle Tim and his wife came out to speak. Afterwards, he told us we were the best band he’d ever seen. We felt pretty good about that. Young people in Boulder and Denver and around Colorado treated us like favorite siblings, supporting us and encouraging us to keep on. Years later we paid many a due in the bars of Colorado, but not with the early Zephyr; it was like riding a wave.

Another band came to Boulder at the same time we did, and they were a big influence on all of us over the years: Freddi and Henchi and the Soulsetters (now The Freddi-Henchi Band). They were an R&B band from Phoenix who played and danced and sang and acted up with great good humor, wit, and talent. All of us considered it an honor to be called up to jam with them. Tommy, Candy, and I played together for the last time jamming with them. Freddie Gowdy, the lead singer, is one of the best singers I’ve ever heard. He and Candy were great friends and admirers of each other. I hope he gets a break some day.

AV: Discuss the role of Barry Fey with Zephyr.

DG: When we got Zephyr together, one of our more money oriented friends arranged for Barry to hear us play. We went down to a bar owned by Barry’s partner, Nate Feld, in Denver early in the afternoon of a day in April, 1969 and set up and played a few songs for him. Barry knew Tommy from his nightclub, The Family Dog, Denver’s early psychedelic ballroom, where Tommy’s band had opened the shows from time to time. We played well, as we always did during this period, and Barry’s words, as we walked up to his table afterward were, ”Well, Tommy, you’ve really got something this time.” He told us that each of us was great. (Except for me; he said he didn’t know enough about bass to know if I was good or not. Tommy told him I was good.) and that he thought he could put us right into the big time. He wanted to make some calls and then get back with us. Barry’s genius is that he seems so sincere. We were sure we were on a smooth road to rock and roll nirvana.

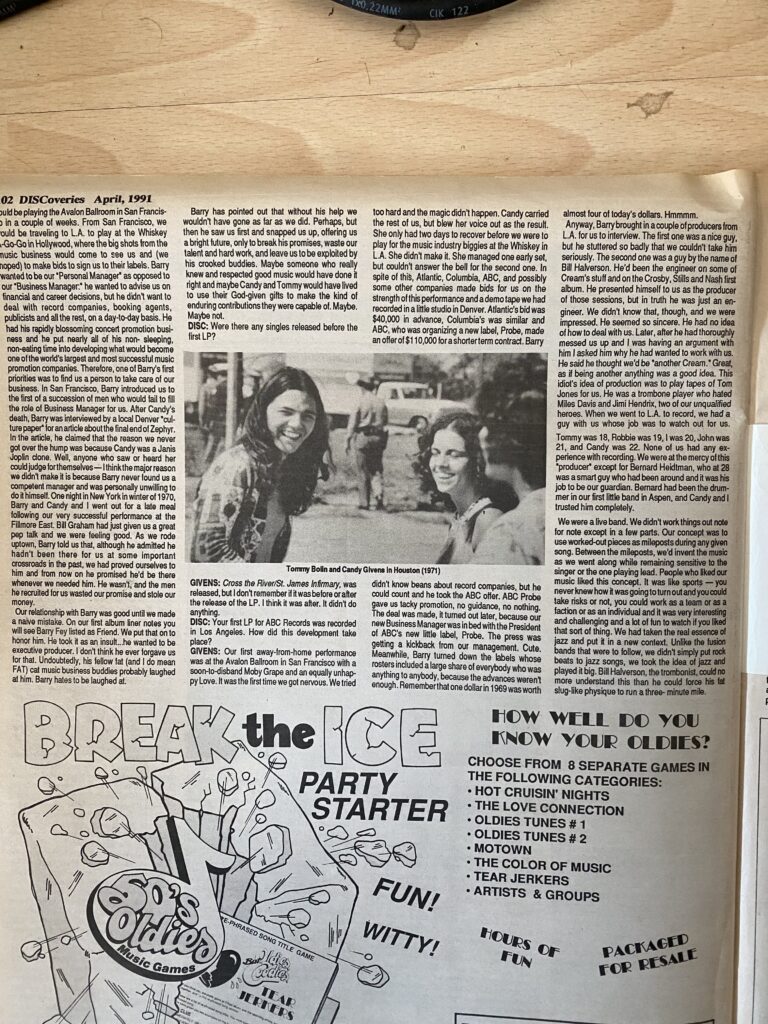

He called us the following day with the news that we would be playing at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco in a couple of weeks. From San Francisco, we would be traveling to L.A. to play at the Whiskey A-Go-Go in Hollywood, where the big shots from the music business would come to see us and (we hoped) to make bids to sign us to their labels. Barry wanted to be our “Personal Manager” as opposed to our “Business Manager.” He wanted to advise us on financial and career decisions, but he didn’t want to deal with record companies, booking agents, publicists and all the rest, on a day to day basis. He had his rapidly blossoming concert promotion business and he put nearly all of his non-sleeping, non-eating time into developing what would become one of the world’s largest and most successful music promotion companies. Therefore, one of Barry’s first priorities was to find us a person to take care of our business. In San Francisco, Barry introduced us to the first of a succession of men who would fail to fill the roll of business manager for us. After Candy’s death, Barry was interviewed by a local Denver “culture paper” for an article about the final end of Zephyr. In the article, he claimed that the reason we never got over the hump was because Candy was a Janis Joplin clone. Well, anyone who saw or heard her could judge for themselves. I think the major reason we didn’t make it is because Barry never found us a competent manager and was unwilling and probably unable to do it himself. One night in New York in Winter 1970, Barry, Candy, and I went out for a late meal following our very successful performance at the Fillmore East. Bill Graham had just given us a great pep talk and we were feeling good. As we rode uptown, Barry told us that, although he admitted he hadn’t been there for us at some important crossroads in the past, we had proved ourselves to him and from now on he promised he’d be there whenever we needed him. He wasn’t, and the men he recruited for us wasted our promise and stole our money.

Our relationship with Barry was good until we made a naive mistake. On our first album liner notes you will see Barry Fey listed as Friend. We put that on to honor him. He took it as an insult… he wanted to be Executive Producer. I don’t think he ever forgave us for that. Undoubtedly, his fellow fat (and I do mean FAT) cat music business buddies probably laughed at him. Barry hates to be laughed at.

Barry has pointed out that without his help we wouldn’t have gone as far as we did. Perhaps, but then he saw us first and snapped us up, offering us a bright future, only to break his promises, waste our talent and hard work, and leave us to be exploited by his crooked buddies. Maybe someone who really knew and respected good music would have done it right and maybe Candy and Tommy would have lived to use their God-given gifts to make the kind of enduring contributions they were capable of. Maybe. Maybe not.

AV: Were there any singles released before the first LP?

DG: “Cross the River’ (and B-side “St. James Infirmary”) was released, but I don’t remember if it was before or after the release of the LP. I think it was after. It didn’t do anything.

AV: Your first LP for ABC Records was recorded in Los Angeles. How did this development take place?

DG: Our first away-from-home performance was at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco with a soon-to-disband Moby Grape and an equally unhappy Love. It was the first time we got nervous. We tried too hard and the magic didn’t happen. Candy carried the rest of us, but she blew her voice out in the process. She only had two days to recover before we were to play for the Music Industry Biggies at the Whiskey in L.A. She didn’t make it. She managed one early set but couldn’t answer the bell for the second one. In spite of this, Atlantic, Columbia, ABC, and possibly some other companies, made bids for us on the strength of this performance and a demo tape we had recorded in a little studio in Denver. Atlantic’s bid was $40,000 in advance, Columbia’s was similar and ABC, who was organizing a new label Probe, made an offer of $110,000 for a shorter term contract. Barry didn’t know beans about record companies, but he could count and he took the ABC offer. ABC/Probe gave us tacky promotion, no guidance, no nothing. The deal was made, it turned out later, because our new “Business Manager” was in bed with the President of ABC’s new little label Probe. The Press was getting a kickback from our management. Cute. Meanwhile Barry turned down the labels whose rosters included a large share of everybody who was anything to anybody, because the advances weren’t high enough. Remember that one dollar in 1969 was worth almost four 1988 dollars. Hmmmm.

Anyway, Barry brought in a couple of producers from L.A. for us to interview. The first one was a nice guy, but he stuttered so badly that we couldn’t take him seriously. For years, Candy and I could make each other laugh by calling a studio a “stoo-oo-ooooo-di-o’’ in honor of this unfortunate man. I recall John Faris remarking that the studio bills would be seriously inflated because we’d be waiting while the man tried to talk to us. The second one was a guy by the name of Bill Halverson. He’d been the engineer on some of Cream’s stuff and on the Crosby, Stills and Nash first album. He presented himself to us as the producer of those sessions, but in truth he was just an engineer. We didn’t know that, though, and we were impressed. He seemed so sincere. He had no idea of how to deal with us. Later, after he had thoroughly messed us up and I was having an argument with him I asked him why he had wanted to work with us. He said he thought we’d be “another Cream.” Great, as if being another anything was a good idea. This idiot’s idea of production was to play tapes he’d recorded of Tom Jones jamming with some L.A. studio musicians for us, hoping we’d catch on. He was a fat slob ex-trombone player who hated Miles Davis and Jimi Hendrix, two of our unqualified heroes. When we went to L.A. to record, we had a guy with us whose job was to watch out for us. Tommy was 18, Robbie was 19, I was 20, John was 21, and Candy was 22. None of us had any experience recording. We were at the mercy of this “producer” except for Bernard Heidtman, who at 28 was a smart guy who had been around and it was his job to watch out for us. Bernard had been the drummer in our first little band in Aspen, and Candy and I trusted him completely.

We were a live band. We didn’t work things out note for note except in a few parts. Our concept was to use worked out pieces as mileposts during any given song. Between the mileposts, we’d invent the music as we went along while remaining sensitive to the singer or the one playing lead. People who liked our music liked this concept. It was like sport — you never knew how it was going to turn out and you could take risks or not, you could work as a team or as a faction or as an individual, and it was very interesting and challenging and a lot of fun to watch if you liked that sort of thing. We had taken the real essence of jazz and put it in a new context. Unlike the jazz fusion bands that were to follow, we didn’t simply put rock beats to jazz “songs,” we took the idea of jazz and played it BIG. Bill Halverson, the trombonist, could no more understand this than he could force his fat slug-like physique to run a three minute mile.

During the two days following our arrival in L.A, we recorded good versions of everything we knew. Halverson was an employee of Wally Heider Studio where we were recording and was about to disappoint his boss, Wally, to whom he had promised a fat recording bill. A couple of months earlier, we had recorded a three song demo tape for the record companies. We had taken first or second takes of each song. I think we spent maybe $250 on it. The local “underground” station in Denver had played the tape on the air. It was the most requested piece of music they had ever had at the station. Bernard knew this and was determined not to let Halverson destroy the music by taking it apart in the studio. Unfortunately for us, Bernard came down with hepatitis and was confined to his room for three weeks while we worked at Bill Halverson’s mercy. We trusted old Bill and so we threw out what we had recorded and started the harrowing experience of destroying ourselves.

Halverson was working all day from eight or nine in the morning with studio customers, then bringing us in during the evenings, subject to the whims of Steve Stills or whatever other rock-god wanted to push us out. When he wasn’t speeding, he was so tired that on occasion he fell asleep at the console. One night he was so soundly asleep that Candy, Tommy, and I wheeled him up and down the hallways in his chair. We banged him into walls and he still never woke up. He was about 84” and about 250 pounds. We laughed so hard, we thought we were going to blow up. Little did we know the joke was on us… this album was not going to be good. We wanted to adapt our music to the studio environment, but we didn’t know how and neither did Halverson. For years, Bernard has said that if we had kept those first takes, the ones Halverson threw away, we’d have had it made. We were not competent studio musicians nor was Candy a studio singer. We could create magic, though, and we had proved it again and again in front of people and even once on tape, but not much got on our first album.

AV: The eponymous Zephyr LP was distinctive for several reasons. First of all, the rainbow bathroom cover and the fish-eyed inside liner photo were first rate. Explain how these were obtained.

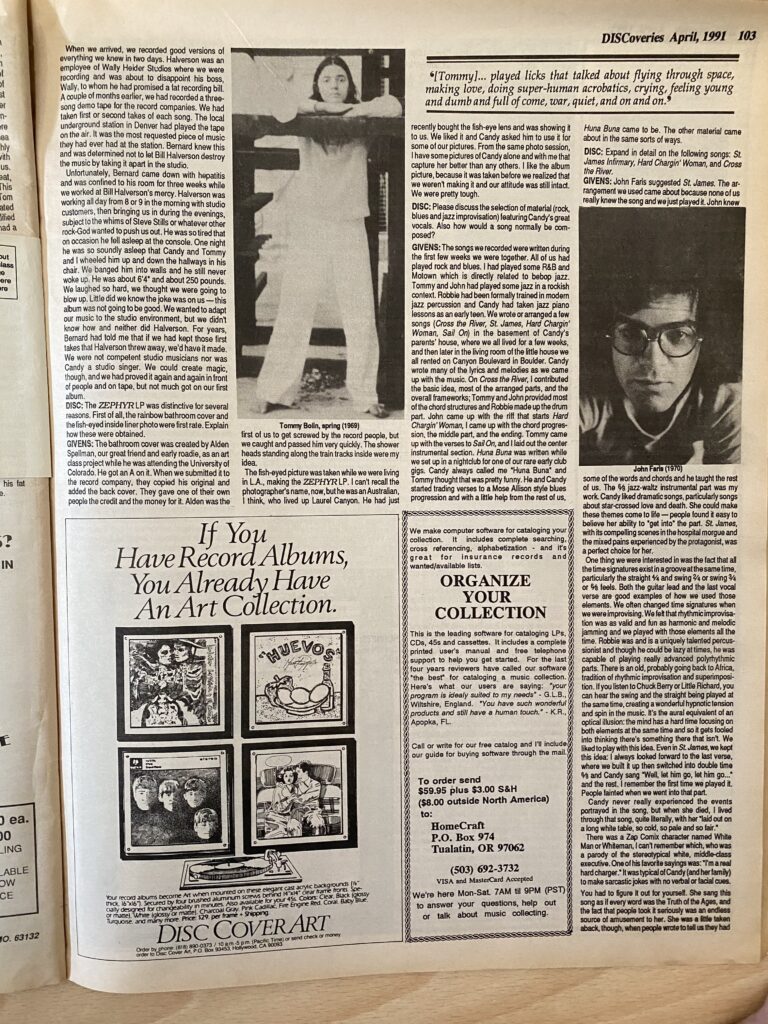

DG: The bathroom cover was created by Alden Spellman, our great friend and early roadie, as an art class project while he was attending the University of Colorado. He got an A on it. When we submitted it to the record company, they copied his original and added the back cover. They gave one of their own people the credit and the money for it. Alden was the first of us to get screwed by the record people, but we caught and passed him very quickly. The shower heads standing along the train tracks inside were my idea.

The fish-eye picture was taken while we were living in L.A., making the Zephyr LP. I can’t recall the photographer’s name, now, but he was an Australian, I think, who lived up Laurel Canyon. He had just recently bought the fish-eye lens and was showing it to us. We liked it and Candy asked him to use it for some of our pictures. From the same photo session, I have some pictures of Candy alone and with me that captures her better than any others. I like the album picture, because it was taken before we realized that we weren’t making it and our attitude was still intact. We were pretty strong.

AV: Please discuss the selection of material featuring Candy’s great vocals arranged around material that covered rock, blues, and jazz (e.g., “Cross the River,” “St. James,” and “Huna Buna”) improvisation with all compositions by Zephyr except “St. James” and “Raindrops.” Also, how would a song normally be composed?

DG: The songs we recorded were written during the first few weeks we were together. All of us had played rock and roll and blues. I had played some R&B and Motown which is directly related to bebop jazz. Tommy and John had played some jazz in a rockish context. Robbie had been formally trained in modern jazz percussion and Candy had taken jazz piano lessons as an early teen-ager. We wrote or arranged a few songs (“Cross the River,” “St. James,” “Hard Chargin’ Woman,” and “Sail On”) in the basement of Candy’s parents’ house, where we all lived for a few weeks, and then later, in the living room of the little house we rented together on Canyon Boulevard in Boulder. Candy wrote many of the lyrics and melodies as we came up with the music. She worked with our roommate, Frank Anton, who was never credited, but I think he was probably a big help. On “Cross the River,” I contributed the basic idea, most of the arranged parts, and the overall frameworks; Tommy and John provided most of the chord structure; and Robbie made up the drum part. John came up with the riff that starts “Hard Chargin’ Woman” and I came up with the chord progression, the middle part, and the ending. Tommy came up with the verses to “Sail On” and I laid out the center instrumental section. “Huna Buna” was written while we set up in a night club for one of our rare early club gigs. Candy always called me “Huna Buna” and Tommy thought that was pretty funny. He and Candy started trading verses to a Mose Allison style blues progression and, with a little help from the rest of us, “Huna Buna” came to be. The other material came about in the same sorts of ways.

AV: Expand in detail l on the following songs: “St. James Infirmary,” “Hard Chargin’ Woman,” and “Cross the River.”

DG: John Faris suggested “St. James.” The arrangement we used came about because none of us really knew the song and we just played it. John knew some of the words and chords and he taught the rest of us. Switching into the 6/8 jazz-waltz instrumental part was my idea. Candy liked dramatic songs, particularly songs about star-crossed love and death. She could make these themes come to life — people found it easy to believe her, thanks to her ability to “get into’’ the part. “St. James,” with its compelling scenes in the hospital morgue and the grief expressed by the protagonist, was a perfect choice for her.

One of the things we were interested in was the fact that all the time signatures exist in a groove at the same time, particularly the straight 4/4 and swing 2/4 or swing 3/4 or 6/8 feels. Both the guitar lead and the last vocal verse are good examples of how we used those elements. We often changed time signatures when we were improvising. We felt that rhythmic improvisation was as valid and fun as harmonic and melodic jamming, and we played with those elements all the time. Robbie was and is a uniquely talented percussionist and, though he could be lazy at times, he was capable of playing really advanced polyrhythmic parts. There is a very old, probably going back to Africa, tradition of rhythmic improvisation and superimposition. If you listen to Chuck Berry or Little Richard, you can hear the swing and the straight being played at the same time, creating a wonderful hypnotic tension and spin in the music. It’s the aural equivalent of an optical illusion: the mind has a hard time focusing on both elements at the same time and so it gets fooled into thinking there’s something there that isn’t. We liked to play with this idea. Even in “St. James” we kept this idea: I always looked forward to the last verse, where we built it up then switched into double time 6/8 and Candy sang, “Well, let him go, let him go…” and the rest. I remember the first time we played it. People fainted when we went into that part.

Candy never really experienced the events portrayed in the song, but when she died, I lived through that song, quite literally, with her “laid out on a long white table, so cold, so pale and so fair.”

There was a Zap Comix character named “White Man” or “Whiteman,” I can’t remember which, who was a parody of the stereotypical white, middle-class businessman. One of his favorite sayings was: “I’m a real hard charger.” It was typical of Candy (and her family) to make sarcastic jokes with no verbal or facial cues. You had to figure it out for yourself. She sang this song as if every word was the Truth of the Ages, and the fact that people took it seriously was an endless source of amusement to her. She was a little taken aback, though, when people wrote to tell us that they had used that song for both weddings and funerals. At any rate, we had a good time playing the song: the intro still gets me twenty years later. It was a sure thing that people would cheer when we started into it. Once again, we switched from one feel to another while keeping the same pulse. We were using rhythmic changes along with the harmonic progressions to make changes in intensity. This song also gave birth to Tommy’s unaccompanied Echoplex guitar solos. Jimmy Page had done some real basic echo solos during Led Zeppelin’s first couple of tours, but nothing like the extravaganzas Tommy came up with. He was producing sounds and rhythms that no one had heard before. I’ve heard his influence again and again through the years, but I don’t think anyone has caught up yet. The guitarist in KISS copied Tommy’s solos almost exactly.

I find myself smiling as I think of the times John and I would run off the stage while Tommy did his solo. We’d smoke a cigarette or two and watch from the wings as Tommy took the audience for a tour of Echo Beat Land. When he was nearly finished, he played us a cue that said, “Come back, now” and we’d hop back up and dig in for the rest of it. At the end of the song, we played the same three chord round while Candy vamped on top. Robbie Chamberlin came up with a drum beat that managed to sound rock-steady even though we increased the tempo all the way to the end of the song. Candy liked this part and she’d go on as long as she could, while Tommy and I gritted our teeth and tried to find new ways to play the same three chords harder and faster over and over. John took his normal position: providing color and texture to the music. We took the ending right from Procol Harum’s “Repent Walpurgis.” It was big and strong and it felt really good to do it. We used to end our sets with this song because we couldn’t follow it. (Neither could a lot of the people we preceded on the bill.) Wish we had got it right on tape.

“Cross the River” was our set opener. It started life as a blues jam Candy and I often played with Brown Sugar, the band we had prior to Zephyr. I had been fooling around with that beat, but our drummer couldn’t play it. When we started Zephyr and needed songs, I pulled it out at one of our first rehearsals. Robbie came up with the exact right drum part and the rest of it fell into place. Live, the middle part was very volatile and it went someplace new nearly every time we played it. For the LP, though, Halverson had us play it so many times that it lost some of the spontaneity that it should have had. However, I think we broke some ground with this song. The arrangement owes a debt to “Electric Lady” era Jimi Hendrix, but I think Candy’s original metal-woman vocals, the groove, and particularly the swinging walking bass/be-bop style guitar solo were something new for rock and roll. Once again, we switched from one rhythm to another, as if moving from one overlay to another, always keeping the same basic pulse that we started with.

Candy’s lyrics still haunt me. Now and then I’ll recall those words and I’ll see in my mind’s eye the same bad-dream images I saw the first time she read them to me. She told me that she thought she had always been sensitive to the “spirit” worlds and that she felt she had to keep her guard up because beings there tried to influence her. She was a very practical and down-to-Earth woman and I believe she was quite serious about this. The words in “Cross the River’’ are about her feelings about her confrontation with the dark and hidden side of existence.

AV: Discuss the Denver Pop Festival.

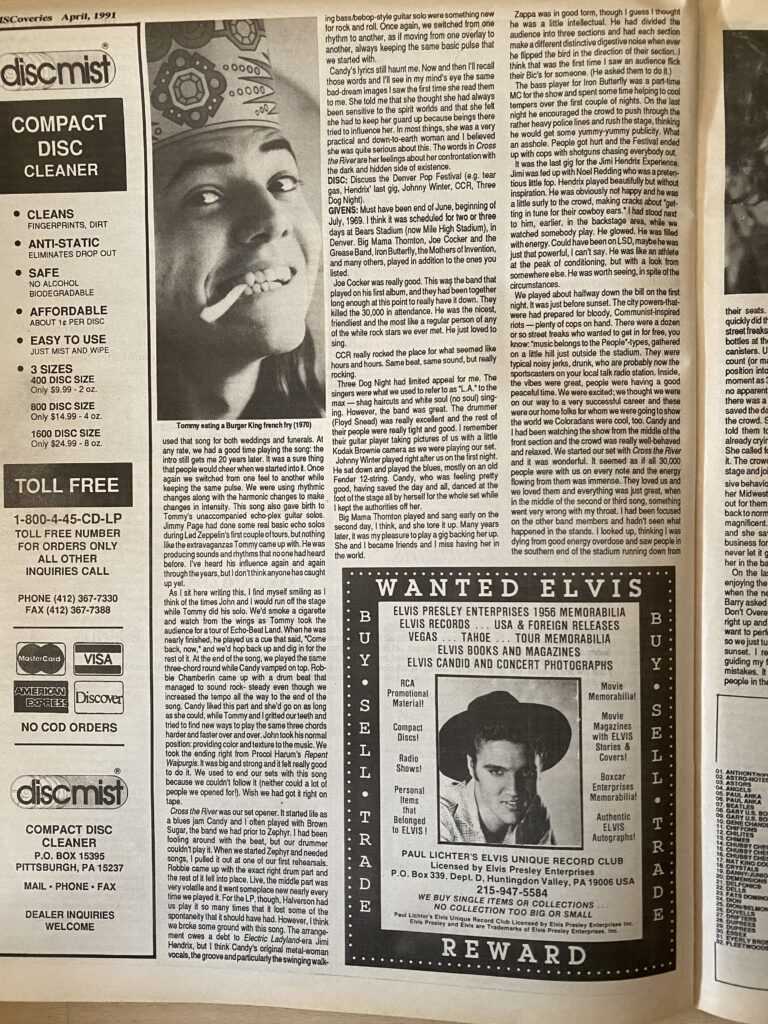

DG: Must have been end of June, beginning of July, 1969. I think it was scheduled for two or three days at Bears Stadium (now Mile High Stadium) in Denver. Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Winter, Three Dog Night, Big Mama Thornton. Joe Cocker and the Grease Band, Iron Butterfly, the Mothers of lnvention, and many others.

Joe Cocker was really good. This was the band that played on his first album, and they had been together long enough at this point to really have it down. They killed the 30,000 in attendance. He was the nicest, friendliest, and the most like a regular person of any of the white rock-stars we ever met. He just loved to sing.

CCR really rocked the place for what seemed like hours and hours. Same beat, same sound, but really rocking.

Three Dog Night had limited appeal for me. The singers were what we used to refer to as “L.A.” to the max: shag haircuts and white soul (no soul) singing. However, the band was great. The drummer (Floyd Sneed) was really excellent and the rest of their people were really tight and good. I remember their guitar player taking pictures of us with a little Kodak Brownie camera as we were playing our set.

Johnnie Winter played right after us on the first night. He sat down and played the blues, mostly on an old Fender 12-string. Candy, who was feeling pretty good, having saved the day and all, danced at the foot of the stage all by herself for the whole set while I kept the authorities off her.

Big Mama Thornton played and sang early on the second day, I think, and she tore it up. Many years later, it was my pleasure to play a gig backing her up. She and I became friends and I miss having her in the world.

Zappa was in good form, though I guess I thought he was a little intellectual. He had divided the audience into three sections and had each section make a different distinctive digestive noise whenever he flipped the bird in the direction of their section. I think that was the first time I saw an audience flick their BIC’s for someone. (He asked them to do it.)

The bass player for Iron Butterfly was a part time MC for the show and spent some time helping to cool tempers over the first couple of nights. On the last night he encouraged the crowd to push through the rather heavy police lines and rush the stage, thinking he would get some yummy-yummy publicity. What an asshole. People got hurt and the “Festival” ended up with cops with shotguns chasing everybody out.

It was the last gig for the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Jimi was fed up with Noel Redding who was a pretentious little fop. Hendrix played beautifully, but without inspiration. He was obviously not happy and he was a little surly to the crowd, making cracks about “getting in tune for your cowboy ears.” I had stood next to him, earlier, in the back stage area, while we watched somebody play. He glowed. He was filled with energy. Could have been on LSD; maybe he was just that powerful, I can’t say. He was like an athlete at the peak of conditioning, but with a look from somewhere else. He was worth seeing, in spite of the circumstances.

We played about half-way down the bill on the first night. It was just before sunset. The city powers-that-were had prepared for bloody, Communist inspired riots: plenty of cops on hand. There were a dozen or so street freaks who wanted to get in for free; you know, “music belongs to The People” types, gathered on a little hill just outside the stadium. They were typical noisy jerks, drunk, who are probably now the sportscasters on your local talk radio station. Inside, the vibes were great, people were having a good peaceful time. We were excited; we thought we were on our way to a very successful career and these were our home folks for whom we were going to show the world that we Coloradans were cool, too. Candy and I had been watching the show from the middle of the front section and the crowd was really well behaved and relaxed. We started our set with “Cross the River” and it was wonderful. It seemed as if all 30,000 people were with us on every note and the energy flowing from them was immense. They loved us and we loved them and everything was just great when, in the middle of the second or third song, something went very wrong with my throat. I had been focused on the other band members and hadn’t seen what happened in the stands. I looked up, thinking I was dying from good energy overdose and saw people in the south end of the stadium running down from their seats. It reminded me of flowing water, they poured so quickly out of the tiers of bleachers. The street freaks outside had started throwing empty wine bottles at the cops. The police replied with tear gas canisters. Unfortunately, they forgot to take into account (or maybe not) the breeze blowing from their position into the stadium. It was an extremely ugly moment as 30,000 closed in people were gassed for no apparent reason. The good mood went “poof and there was a sudden violence in the air. Then Candy saved the day. She stopped the song and looked into the crowd. She called them down onto the field and told them to “stay cool” and that, “Since we were already crying, might as well sing a good blues song.” She called for “St. James Infirmary” and we rolled into it. The crowd spread out all around the flatbed-truck stage and joined together in a rejection of the aggressive behavior that had almost erupted. She gathered her midwest people around her and sang her heart out for them for another forty-five minutes while things got back to normal in the local atmosphere. She was truly magnificent. She saved a lot of people a lot of pain and she saved Barry Fey’s ass and probably his business for him. He was thrilled at the time, but he never let it get in the way when it came to stabbing her in the back later on.

On the last night, we were sitting in the stands enjoying the show and feeling good about ourselves when the next group on the bill failed to show up. Barry asked us if we would play again (this from Mr. Don’t Overexposem) in their place. We hopped right up and played another beautiful set. We didn’t want to perform an instant replay of our earlier set, so we just turned loose and jammed for a while as the sun set. I remember feeling as if something was guiding my fingers — everything came out right, no mistakes. It was easy and fine and powerful. The people in the audience and the people on the stage were not separated by any kind of artificial pretense; we played for them and they gave us the energy to get higher. Everybody there knew that a new star was born and we were all cruising into a happy new era together. Oh, well.

AV: I believe Tommy Bolin left to join a band called Energy. Please discuss Tommy Bolin’s career in detail from Zephyr (including his personality and musical ability — I believe he was kicked out of a Sioux City, Iowa high school for not cutting his hair — as well as how his departure affected Zephyr), on to Energy, replacing Joe Walsh in the James Gang, Billy Cobham, Deep Purple, his solo work (including the Teaser LP), and his unfortunate death at the age of 25 in a Miami hotel room. Bolin was a prolific songwriter as evidenced by writing or co-writing five of nine tunes for the Zephyr LP, nine of ten for the James Gang Bang LP. Please comment on his songwriting ability which makes one wonder how he could write while having a “drug problem” — or was his drug-related death accidental?

DG: We used to play football in the park in downtown Boulder. Tommy liked to play running back. He was about 5”9 or 5”10 and weighed about 160. Tackling him was serious business — he did not give up and fall down if someone grabbed him. He wanted to win and he wanted to be the star. Tommy loved playing the Prince of Guitars. He was very competitive, a trait which both served and betrayed him. For example, he and Candy worked extremely well together until Candy started getting more recognition than Tommy did. He began to butt in (musically) when she was most intense on stage, where previously he had been content to support her. He couldn’t stand being out of the spotlight. Before playing with us, he had easily dominated any group of musicians he was with, but Candy was smarter, older, wiser, and more charismatic than he was, while she was equally talented. Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Pete Townsend, and, most of all, Jimi Hendrix, had already revolutionized guitar playing; good guitar players weren’t big news anymore. Grace Slick and Janis Joplin were not the same kind of animal Candy was. She was something different and both press and audience tended to pay more attention to her than to Tommy. Tommy didn’t take it very well.

When Zephyr was first together, there were two kinds of behavior that we all frowned upon: ego tripping and pandering to the audience. We played the music we liked and figured that people we liked would like the music. We applied our coldest insult: “he/she/they are commercial” to musicians we felt were only playing music as a job. To us, playing music was serious and important, but you had to be humble and a good person. We talked about it a lot, and four of us agreed that being in our position was good fortune. Tommy thought he deserved it. On the way home from the airport after a week or two of playing one or two nighters around the country, Tommy announced to us that he had decided to go on an “ego-trip.” He did. After that, he was out to promote Tommy and that was the beginning of the end. No more team-mind-reading for us; instead it was Tommy trying to upstage everyone else. Where in the early days, each of us had played a solo, now it was TOMMY playing Echoplex for thirty minutes out of each set. Now, instead of writing songs together, it was Tommy writing in his room for Tommy.

He could play most anything. If you said, “Play something that sounds like it’s from Fiji,” he’d play something that at least sounded like it came from Fiji’s neighborhood if not Fiji itself. He played licks that talked about flying through space, making love, doing super-human acrobatics, crying, feeling young and dumb and full of come, war, quiet, and on and on. He and Candy used to trade licks asking questions and getting answers about all sorts of deeply personal stuff without the need for English language. He was really fun to play music with before he got anxious about getting rich and famous.

We had fired Robbie Chamberlin and brought Bobby Berge to Boulder from South Dakota at Tommy’s behest. Bobby was more basic than Robbie and not as proficient, but Robbie tended toward laziness and we wanted someone who would kick us in the butt back there behind the drums. Robbie, for all his brilliance, had to be prodded if he wasn’t in the mood on a given night. We played with Bobby for about a year. He and Tommy got very close, started getting loaded together and hanging out together. The rest of us were still relatively drug-free, but Tommy and Bobby were getting seriously out there. They started leaving the other three of us out when we were playing, going off on their own loud, and to us, obnoxious, musical flights of whatever. John, Candy, and I had enough and decided we wanted Robbie back. Tommy would have none of that, as there was something about a strip-poker game involving Robbie, Robbie’s girlfriend, and Tommy’s girlfriend while we were in New York making our second album. I told Tommy we would hate to lose him, but the three of us weren’t going to play with Bobby anymore. Tommy said he was sorry, but he and Bobby would go on their own. We played one more short and painful tour with Tommy and that was it.

He and Bobby formed a band they called Energy. They played excruciatingly loud, clunky, pseudo-fusion stuff. Tommy had met Billy Cobham at International Raceway Park in Ona, West Virginia on one of our gigs. Candy’s friend from Golden High School, Doug Lubahn, had a band called Dreams, whose members included the Brecker brothers and Billy Cobham. They were playing on the same show in Ona that night and Doug introduced Tommy to Cobham. When Cobham was signed to make his Spectrum LP, he called Tommy. It was on these sessions that Tommy met Jan Hammer, who played keys on the album. Tommy had spent the past year and a half worshipping John McLaughlin, and he had incorporated a lot of McLaughlin’s angular style into his playing. The success of Cobham’s album encouraged Tommy to head in that direction, but Energy didn’t have the players to pull it off and their audiences were nearly all male guitar players with cotton in their ears. Tommy and Bobby got serious about using drugs during this time. Tommy was pretty miserable. We continued with Zephyr and made another album (Sunset Ride) with an all new band that was critically acclaimed, while Tommy had a band that couldn’t get signed and couldn’t draw flies.

Both Energy and the Sunset Ride incarnation of Zephyr died at about the same time, late 1972. Candy, Tommy, and I had formed a band with the former drummer from Flash Cadillac and the Continental Kids back in 1970. We played oldies only and strictly for fun. The name of the band was “The Legendary 4-Nikators” (pronounced fornicators). It was a great band but only lasted for one gig.

Harold, the drummer, graduated from law-school in 1972 and wanted to play again. He brought Candy, Tommy, John, and me together with some other players to revive the 4-Nikators. After what seemed like decades of artistic pressure, we did anything we wanted to. We played at one club in Boulder on Monday nights, Art’s Bar and Grill. We were making $100 per person per night (1973) and we had nine people in the band. The place was always packed with a line. In Boulder, it was known as the closest thing to a sure thing that you would get lucky if you came to Art’s on Monday night. The cars in the parking lot used to do as much rocking as we did. People disrobed and danced naked on the stage with us — good looking people. Tommy, Candy, John, and I made friends again. We even had a Zephyr reunion one night that was one of our best nights since the beginning. There’s a tape out there; I’d like to get it.

One Monday afternoon, I drove out to Art’s by myself to set up and found Tommy alone inside setting up his amp. He told me that Barry had called him about taking Joe Walsh’s place in the James Gang. Now, the James Gang had always been a cheap laugh in the Zephyr days, and Tommy didn’t want to play with them. Energy was over, though, and his girl friend was after him to make some money. He said that Barry had promised him if he took the job with the James Gang that in a year or so he could make his own album. We laughed at the idea of him playing with them. He was a little embarrassed, but he said he felt he had no choice but to do it. I told him we’d miss him in the 4-Nikators, but good luck. I have a tape of that night around here somewhere, that I listen to every couple of years or so. He and Candy were both great that night — real earthy and soulful. That was the second to last time we played together.

Tommy and his girlfriend moved away from Boulder and only came back once in a while. Whenever I saw him, he was always drunk or high on something. One night, he and I cruised the bars in Boulder drinking water glasses full of 151 proof rum. He wasn’t happy. By this time he had made his Teaser LP, which hadn’t propelled him to rock and roll immortality, and now he was starting with Deep Purple, to him another sellout. He hoped he would get out of it quickly and make another album on his own.

The last time I saw Tommy was about a year before his death. Candy and I were at the Good Earth nightclub in Boulder. Tommy was in town and had come in to jam with Freddie and Henchi, who owned the bar. Freddie called all three of us up to play at the same time. We played real loose and funky, something we hadn’t really done much of before and many smiles were exchanged. It was the last time we played together. Afterwards, Candy and Tommy and I had yet another drink and talked things over. Tommy was almost out on his feet as he spoke. He told us that “we’d been right all along,” that he’d taken over Deep Purple just as Candy and I had taken over Zephyr and that it’s the only way to get anything out of a band. Candy and I looked at each other with question marks on our eyeballs. “Taken over,” really?! And all this time we had thought we had just gotten stuck doing most of the dirty work. After Tommy left, Candy told me he would be dead in a year. He was.

AV: Please discuss the albums Going Back to Colorado, Sunset Ride, and Heartbeat as well as the personnel transitions that occurred. I think you and Candy were the only ones to appear on all four LPs. I also believe Jock Bartley played with Zephyr and later for Firefall.

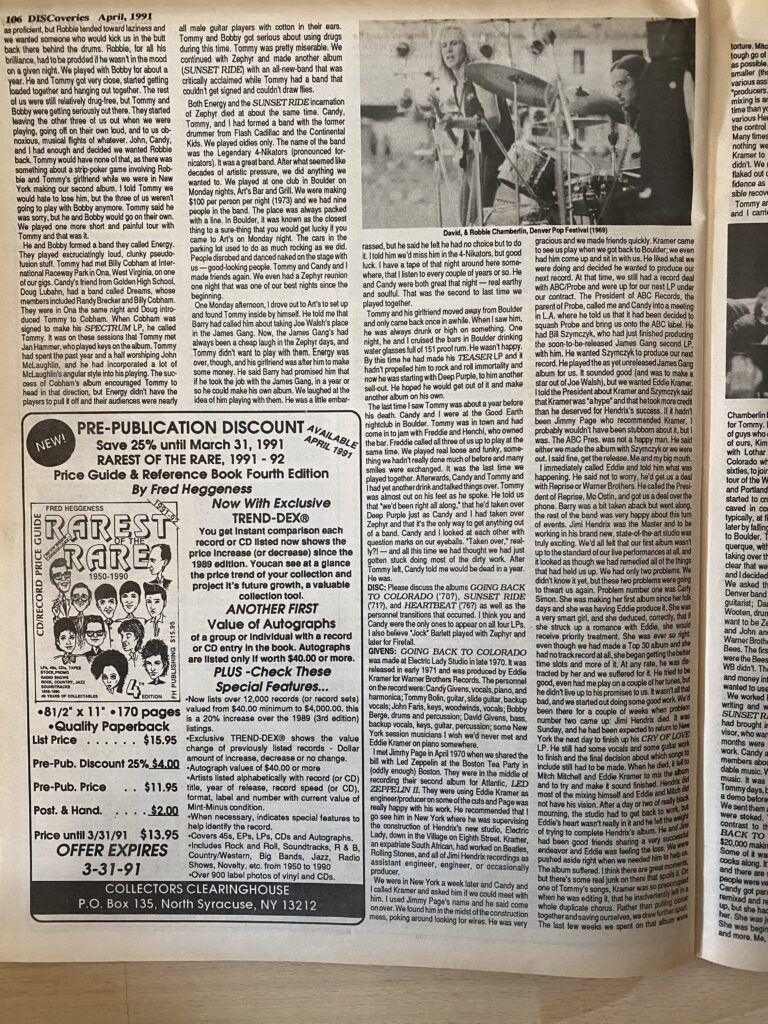

DG: Going Back to Colorado was made at Electric Lady Studio in late 1970. It was released in early 1971. It was produced by Eddie Kramer for Warner Brothers Records. The personnel on the record were: Candy Givens (vocals, piano, and harmonica); Tommy Bolin (guitar, slide guitar, backup vocals); John Faris (keys, woodwinds, vocals); Bobby Berge (drums and percussion); David Givens (bass, backup vocals, keys, guitar, percussion); some New York session musicians I wish we’d never met; and Eddie Kramer on piano somewhere.

I met Jimmy Page in April 1970 when we shared the bill with Led Zeppelin at the Boston Tea Party in (oddly enough) Boston. They were in the middle of recording their second album for Atlantic, Led Zeppelin II. They were using Eddie Kramer as engineer/producer on some of the cuts and Page was really happy with his work. He recommended that I go see him in New York where he was supervising the construction of Hendrix’s new studio, Electric Lady, down in the Village on Eighth Street. Kramer, an expatriate South African, had worked with the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and all of Jimi Hendrix’s recordings as assistant engineer, engineer, or occasionally producer.

We were in New York a week later and Candy and I called Kramer and asked him if we could meet with him. I used Jimmy Page’s name and he said come on over. We found him in the midst of the construction mess, poking around looking for wires. He was very gracious and we made friends quickly. Kramer came to see us play when we got back to Boulder; we even had him come up and sit in with us. He liked what we were doing and decided he wanted to produce our next record. At that time, we still had a record deal with ABC/Probe and we were up for our next LP under our contract. The President of ABC Records, the parent of Probe called me and Candy into a meeting in L.A. where he told us that it had been decided to squash Probe and bring us onto the ABC label. He had Bill Szymczyk, who had just finished producing the soon to be released James Gang second LP, with him. He wanted Szymczyk to produce our next record. He played the as yet unreleased James Gang album for us. It sounded good (and was to make a star out of Joe Walsh), but we wanted Eddie Kramer. I told the President about Kramer and Szymczyk said that Kramer was “a hype” and that he took more credit than he deserved for Hendrix’s success. If it hadn’t been Jimmy Page who recommended Kramer, I probably wouldn’t have been stubborn about it, but I was. The ABC Pres was not a happy man. He said either we made the album with Syzmczyk or we were out. I said fine, get the release. Me and my big mouth.

I immediately called Eddie and told him what was happening. He said not to worry, he’d get us a deal with Reprise or Warner Brothers. He called the President of Reprise, Mo Ostin, and got us a deal over the phone. Barry was a bit taken aback but went along; the rest of the band was very happy about this turn of events. Jimi Hendrix was the Master and to be working in his brand new, state-of-the-art studio was truly exciting. We’d all felt that our first album wasn’t up to the standard of our live performances at all, and it looked as though we had remedied all of the things that had held us up. We had only two problems. We didn’t know it yet, but these two problems were going to thwart us again. Problem number one was Carly Simon. She was making her first album since her folk days and she was having Eddie produce it. She was a very smart girl, and she deduced, correctly, that if she struck up a romance with Eddie, she would receive priority treatment. She was ever so right: even though we had made a Top 30 album and she had no track record at all, she began getting the better time slots and more of it. Eddie is not the most macho of men and I suppose that fucking a big horse of a woman like Carly did something wonderful for his ego. At any rate, he was distracted by her and we suffered for it. He tried to be good, even had me play on a couple of her tunes, but he didn’t live up to his promises to us. It wasn’t all that bad, and we started out doing some good work. We’d been there for a couple of weeks when problem number two came up: Jimi Hendrix died. It was Sunday, and he had been expected to return to New York the next day to finish up his Cry of Love LP. He still had some vocals and some guitar work to finish and the final decision about which songs to include still had to be made. When he died, it fell to Mitch Mitchell and Eddie Kramer to mix the album and to try and make it sound finished. Hendrix did most of the mixing himself and Eddie and Mitch did not have his vision. After a day or two of really black mourning, the studio had to get back to work, but Eddie’s heart wasn’t really in it and he felt the weight of trying to complete Hendrix’s album. He and Jimi had been good friends, sharing a very successful endeavor and Eddie was feeling the loss. We were pushed aside right when we needed him to help us. The album suffered. I think there are great moments, but there’s some real junk on there that spoils it. On one of Tommy’s songs, Kramer was so preoccupied when he was editing it, that he inadvertently left in a whole duplicate chorus. Rather than pulling closer together and saving ourselves, we drew further apart. The last few weeks we spent on that album were torture. Mitch Mitchell and Eddie were having a very tough go of it and wanted as much time in the studio as possible. Eddie began forcing us to use the much smaller (though equally expensive) Studio B with various assistant (read: inexperienced) engineers as “producers.” We had to mix in Studio A, however, and mixing is an inexact sort of thing that can take more time than you might expect. Many times, Mitchell and various Hendrix hangers-on would be crowding into the control room toward the end of our allotted time. Many times Candy and I were furious, but there was nothing we could do — we had no way to force Kramer to live up to his commitment to us and he didn’t. We needed his direction and best efforts. We paid him for his direction and best efforts. He flaked out on us. After this album bombed, our confidence as a band diminished past the point of possible recovery. Time was running out for us.

Tommy and Bobby left in early 1971. Candy, John, and I carried on for a while. We brought Robbie Chamberlin back and began to look for a replacement for Tommy. No luck. After auditioning a whole string of guys who couldn’t cut it, we decided to ask a friend of ours, Kim King, who had been the lead guitarist with Lothar and the Hand People, a band from Colorado who had moved to New York in the late 60s, to join us. Kim accepted and we played a short tour of the West Coast. He did a great job in Seattle and Portland, but when we got to San Francisco, he started to crumble. Our next stop was L.A. and he caved in completely. He was using cocaine and typically, at first, it was a real aid to him, but he paid later by falling apart. We let him go when we returned to Boulder. The four of us played one job, in Albuquerque, with no guitarist at all. Candy saved us by taking over the show and people liked us, but it was clear that we had to do something different. Candy and I decided to start a new band with all new people. We asked three of the members of a good local Denver band to join us: Jock Bartley (later of Firefall), guitarist; Danny Smyth, keyboards; and Michael Wooten, drummer. We didn’t want to be ZEPHYR anymore. Zephyr was Tommy, John, Bobby, and Robbie and us, so we approached Warner Brothers with the idea of calling ourselves “The Bees.” The first time we performed with this band, we were The Bees and people thought it was a good idea. WB didn’t. They thought that they had invested time and money into the name “Zephyr” (true) and that they wanted to use it. End of The Bees.

We worked hard all through the summer of 1971, writing and working out what would become our Sunset Ride LP. Fey was still involved, but he had brought in a multimillionaire stock market advisor, who wanted to be cool, as our “manager.” Those months were a very happy time and we did good work. Candy and I learned a lot from our new band members about the nuts and bolts of making recordable music. We taught them a lot about performing music. It was something entirely different from the Tommy days, but it was strong. Warner’s had us make a demo before they would go ahead with the album. We sent them a tape from our rehearsal hall and they were stoked. They let me be the Producer and in contrast to the $150,000 we spent on Goin’ Back to Colorado, we spent under $20,000 making Sunset Ride, a better album. Some of it is kind of goofy, but some of it really cooks along. It’s still played on the radio in Colorado and there are still people who love it. Our business people were very happy with the first mix I sent them. Candy got paranoid and changed some vocals and remixed and re-mastered the album. She screwed it up, but she had the power to do it and I couldn’t stop her. She was just beginning to lose her confidence. She was beginning to use drugs and alcohol more and more. Me, too. Too bad. Anyway, the album got great reviews and the radio stations around the country said things like: “It’s the best they’ve done so far” and “We love it.” Our little amateur manager couldn’t get us a booking agent though, so we set out on our own to promote this thing. We toured Texas (by this time we had added John Faris and Robbie Chamberlin, and Michael Wooten had quit) and Louisiana. By the time we got home, two months later, we’d had enough of not getting our money and overcrowded motor homes, and each other. Candy and I retired. It turned out that a good agent at William Morris Agency had heard the album and had been trying to track us down for over a month. By the time he called us, we had quit. Our life was like that. Candy and I had many adventures during the years 1972 through 1974. We didn’t play music much, but when we did, it was fun and we were getting real good. We had a few little bands that made us enough money to scrape by on. By 1975 we had built a business out of playing our music in the bars and nightclubs of Colorado. We played our own music still, but always near home. We always planned to get “good enough” to make it again. We had some terrific bands over those years, but they had short life spans and we didn’t ever get “good enough.” A lot happened. Then in 1981 we got the opportunity we had wanted. A local businessman wanted to manage us and make an independently produced album. It could have worked, but by this time Candy had lost control of her drug and alcohol abuse problems and once again we went down in flames. Heartbeat, like all of our records, has its moments. “Secret” is one of my favorite all-time Zephyr songs, but overall the record is weak. We played one little tour of Colorado after the local release of the LP in late 1982. The last Zephyr job was in a little mountain town called Montrose. The old auditorium was full of young kids, mostly girls, who screamed through our set as if the Beatles was playing. Candy left with her new boyfriend as soon as we got home. She spent most of 1983 in Mexico, near Cancun, in a house on the beach with her dope-dealer boyfriend. She had some fun, but when they got drunk, they fought and he was a lot bigger than she was.

AV: The first time we spoke was 1/27/88, which was four years to the day after Candy’s death. Please discuss her personality, musical ability (incredible voice), and the circumstances of this Hard Chargin’ Woman’s death. Also, do you see the opening lines of “Sail On” as ironically prophetic for Candy: “A volcano of dreams of life’s slowly fading/has erupted and flowed throughout the night/And living or not I must go on sailing/and try to escape from the light.”

DG: Candy was as complex as any of us. She was a bundle of contradictory impulses, sometimes afraid, sometimes bold. She was very intelligent and she had educated herself in many areas. She could hold her own in almost any conversation and she could party with the best of them. She sang in front of people for the sixteen years I knew her; it was something she loved to do. The last time I saw her sing, about a week before she died, she came in to jam with the Legendary 4-Nikators. She told me she wanted to come back to Boulder and play with us again, that the 4-Nikators were what she really liked. She sang a medley of Supremes’ songs and she transfixed the crowd. She sang as well as anyone I’ve ever heard. She owned the audience (a rugby player’s ball), they literally stood with their mouths hanging open as she poured her heart into “Stop In the Name of Love,” “Come See About Me,” and “Got Him Back in My Arms Again.” She looked over at me in the middle of the last song and she winked a little private wink to me to say, “Look at me, H.B., I’m really good now!” She was the best.

Many of the songs Candy performed: “High Flyin’ Bird,” “St. James Infirmary,” “Sail On,” “Cross the River,” and others, seem prophetic to me. I think it is really odd that she sang these songs, then lived them out, rather than the other way around. A minor point, on “Sail On” the words are: “A volcano of dreams, a life slowly fading/has erupted and blown up the night. And living or not, I must go on sailing/and try to escape from the light.”

Candy returned to Boulder from Mexico on or around the 15th of January, 1984. I spent an afternoon with her and we caught up on each other’s experience. She’d been having a mixed time with her boyfriend and was yearning to be a free woman again. We talked about her rejoining the 4-Nikators and making a blues album. She had been drug and alcohol free for a few weeks and she was feeling well. I intended to see her several times that week and we made arrangements to get together at her apartment to watch the Super Bowl on the following Sunday. I was working on a series of computer graphics projects for the Boulder Daily Camera newspaper and had a deadline to meet. I tried to call her, but she had begun partying again and she was either asleep or gone whenever I tried to reach her. My wife and I went to her place on Sunday and the three of us watched the football game. Candy and Judy got bored with the game and got involved in some girl stuff. By the end of the game, Candy was looking tired and was still in her nightgown. We had had a good time and she kissed me goodbye with a little wink when it was time to go. It was the last time I saw her alive.

I tried to talk to her again the following week, but she was never there. I was nervous and felt something hovering over us all. Then on Friday morning my phone rang at 6:00 a.m., a moment after I had awakened from a disturbing dream. The woman on the other end asked me if I knew Candy Givens. I said, “Yes, why?” and she replied that they had her at the hospital in critical condition. She asked me to come to the hospital. Judy and I got up and went over as quickly as we could. When I walked in, a policeman greeted me. He looked very sad. I asked him about Candy and he told me it was too late. The doctor, a young guy, came out and sadly explained that he had done everything he could, but she was dead. Judy started crying and she went to try to comfort Candy’s boyfriend. I asked to see her. I was escorted into a dimly lit back room where she was laid out on a long table, covered by a sheet. I pulled the sheet down and looked at her. Her eyes were only half closed and her face had the expression I had long ago learned meant she had been stoned. I touched her and her body was completely limp. She was not there anymore. I told her goodbye and kissed her and then I pulled the sheet back up and left to find a funeral home.

She had argued with her boyfriend after staying out late drinking with some of her less savory friends. She had locked herself in the bathroom and started to run a tub for the Jacuzzi. She had taken two or three Mexican Quaaludes on top of her tequila high. She lost consciousness in the tub and drowned. Her boyfriend was in the next room the whole time, but by the time he got anxious and broke in, she was gone. I have the feeling that she was very surprised to find herself dead. She had always gotten away with tempting fate… until she died.

AV: How have the deaths of Tommy and Candy affected your outlook on life and your own mortality?

DG: I think of Candy many times every day. I still find it hard to believe that she is gone. I know she’s somewhere, just not here. Occasionally, I see her in dreams. She says she’s doing fine. I really believe we go on after we die, now. My own death seems more real to me now, but I fear it less than I did. All of life’s experience is important to me, good, bad or indifferent. It’s a school. I think I’ll see Candy and Tommy again.

AV: What are the former members of Zephyr doing? Also discuss any current endeavors such as writing or music.

DG: The last I heard, Robbie Chamberlin was playing in Denver with a fairly popular Top 40 band. John Faris has vanished from the face of the Earth — last heard from writing musical scores to porno movies in L.A. in 1982. I’m the Computer Systems Operations Supervisor for a very old, very large law firm in Honolulu. I started there as a word processing temp last July and have been floating upward, looking for my level of incompetence. Computers work like music does in many ways. I still play the guitar nearly every day and I’m a much better musician than I have ever been. One day, perhaps, I’ll go back to it. I’d like to be a writer, though I haven’t the time to do it just yet. Geffen Records is planning to release a Tommy Bolin Anthology this summer, and they are going to include four Zephyr cuts. They say they are going to remix them and release them on CD. I’m hoping they’ll follow through and make those old cuts sound as good as they can.

AV: Many people think of the 60s as a decade that never will be duplicated. Please recount your impressions from one on the inside looking out.

DG: I turned 12 years old in October, 1960. I was 22 when the decade ended. When people speak of the 60’s nowadays, I get the feeling that they are really referring to the period from 1966 to 1972. Maybe just subjective, but I think that the years 1960 through 1965 were a steady progression from the late 50s. In my world, everything really changed in 1965. The old grease/frat wars were ended and drugs began to show up. My friends from school were all a year or two older than I was and many left for Vietnam in the fall of 1965. Many were back before I turned eighteen and my best friends told me how it was jive and to stay away; that our friends were being killed and wounded in vain and that the politicians weren’t going to let the military win. These were young men who had joined the Marines to serve our country. They won medals, they got hurt, and they came back cynical and angry.

Girls started wearing jeans and taking birth control pills in 1963-64, where I lived. Sex was openly discussed and enjoyed. There was the feeling that we were different from all the earlier generations, that our young men and young women were equal in all areas. As a group, we wanted to get rid of the prejudices and stupidity of our elders. We wanted to be smart and honest and competent. I think there was a genuine desire on the part of many people to help people, but there was an arrogant, pompous streak in the culture that soon became hypocrisy.

Drugs opened many doors for us and killed many of us in the process. The effects are all around us today. Particularly distressing to me is the self-consciousness of the popular arts. Art needs to grow out of the common experience of the people, but now with widespread drug use, people have a hard time sharing experience. Drugs make you selfish and self-centered; this is anti-social behavior in its most basic form; drugs and culture don’t mix. They should be used in the proper circumstances by people who are prepared to use them to gain insight. The are not to to be played with. They should not be abused. These are some lessons I learned from this period. LSD sure was fun, though.